"You have enemies? Why, it is the story of every man who has done a great deed or created a new idea. It is the cloud that thunders around everything that shines.

Fame must have enemies, as light must have gnats. Do not bother yourself about it; disdain.

Keep your mind serene as you keep your life clear."

Victor Hugo wrote in his 1845 essay, Villemain.

Walking down the sidewalk hill into Stellarton with my grandmother I noticed she was stepping on every crack. When you’re seven that's a big deal.

“Step on a crack, break your mother’s back”, I sang-songed.

But she kept on.

“Why are you doing that on purpose?” I asked.

“I have my reasons,” she said.

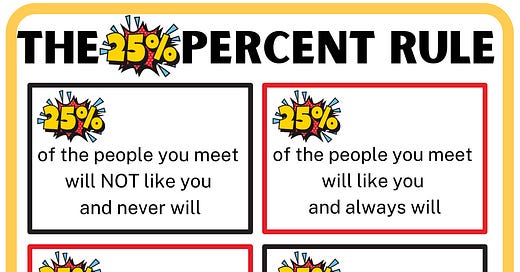

Not everyone you meet in life is going to like you.

And the reverse is also true. You’re not going to like everyone you meet - at first, in the long run, or, for some, ever.

And that’s fine. It doesn’t have to divide us, frighten us, or hold us back from having a good time.

We can relax. The truth is, you will meet very few bad people. Liars, cheats, clinically diagnosables, mean, evil people are just really rare. And all those niche psychology terms folks love to throw around about narcissists, gaslighters, psychopaths and the rest just don’t add up to much but a kind of modern social media ghost story. But they’re like shark attacks. Our experiences with them or stories we’ve heard – all great stories have a villain – have misleading vividness.

In logic, Misleading Vividness is a Logical Fallacy where a small number of dramatic and vivid events are taken to outweigh a significant amount of statistical evidence. A few years back when shark researchers started pointing out that more people are bonked on the head by coconuts than are bitten by sharks, this misleading and oft-misquoted fun fact led local officials in Queensland Australia to cut down the coconut trees on their beaches in 2002 to avoid liability… thereby both proving and totally missing the point of the fallacy of misleading vividness.

Colin Wilson’s landmark book, The Criminal History of Mankind, cites studies that point to roughly:

5% of a given population actively and purposefully doing good (acting altruistically, and playing by the rules) almost without fail,

5% doing evil (or, more accurately, acting selfishly, even criminally so) almost without fail,

And the remaining 90% of us are doing good when we can, obeying rules to our detriment when we have to, but getting away with minor misdeeds to our advantage sometimes, often feeling pretty darn bad about it and going to great lengths to apologize, make amends, and do other kinds of repentance.

The problem is, as Malcolm Gladwell reveals in Talking With Strangers, we’re not just bad at telling who’s who, we’re terrible at it, and it’s evolutionarily ingrained in us to be bad at it. Even simply telling when someone is lying, which many believe they can do, is more fraught than most imagine.

Something is very wrong, Gladwell argues, with the tools and strategies we use to make sense of people we don’t know as well as we could. Our lack of understanding is a big blind spot. And because we don’t know how to talk to strangers, we are inviting conflict and misunderstanding in ways that have a profound effect on our lives and our world.

Admiral H G Rickover, the father of the nuclear navy and one of America’s most outspoken 20th-century critics of modern education, wrote that one of the main central challenges of education should be to understand, appreciate, and learn to live with the fellow inhabitants of our planet. Every child must learn about the races and people of the world and the rich variety of the world's cultures, people, and personalities. They must know something of the history of people and nations. They must learn that there are many people in the world who differ from them profoundly in habits, ideas, and ways of life.

We must perceive these differences, these likes and dislikes, not as occasions for uneasiness or hostility but as challenges to our capacity for understanding.

Eddie Jaku is famously known as the happiest man on earth. He was also a concentration camp survivor. Like Dr. Viktor Frankl, a survivor of Auschwitz, Eddie describes a search for a life's meaning as the central human motivational force with other people at the centre of all thinking.

You get to decide

Whether you like ‘em or they like you or not, are people basically good or bad?

Would you say that the world is a good and safe place or a bad and dangerous place?

You might respond, “It depends on the circumstances,” and that is no doubt (sometimes) true, but go deeper — to your core or “primal” belief.

It’s important because your deep answer is the main thing that determines whether or not you, and by extension, many of those around you, will have a nice life or not.

Our Beliefs Shape Reality

Our beliefs about the world are not shaped by our experiences so much as our “primal beliefs” determine how we interpret those experiences. If our primal belief is that the world is basically a good and safe place, we will likely find positives in even the most difficult circumstances as indicated by Frankl, Jaku, and the testimony of other concentration camp survivors.

If our primal belief is that the people we don’t connect with are all dangerous and the world is a bad and dangerous place, on the other hand, it will color or call into question our interpretation of even the most positive life experiences.

Today leading psychologists like Jer Clifton Ph.D. are exploring how much our basic beliefs shape our lives, our world, and the people in it.

“Broadly speaking, human action may not express who we are so much as where we think we are, and much of what we become in life—much joy and suffering—may depend on the sort of world we think this is.”